Sitting on the 5 bus last weekend, forced with everyone else to listen for twenty minutes to the whining monologue of a young woman, I wondered if this could be regarded as an example of post-communist progress.

As with most aspects of modern life, Hungarians have very quickly caught up with western trends, this extending to the ubiquitous use of the mobile phone. In fact, when the large, brick-like contraptions first came into being, there were probably more of them evident on Budapest’s streets than on the streets of London: for one simple reason - because so many people still had no landline telephone!

Possession of a telephone before 1989 was the major selling point for flats. About one in ten people in Budapest owned one, while in some villages it was only the doctor who did. Waiting lists for acquiring a phone were around 12-15 years – not the apparatus itself, but the line. I was assured that the reasons for this were primarliy (if not entirely) political, inasmuch as communications could hereby be both limited and monitored. Many topics were not deemed safe to discuss on the phone, as for example, matters connected with foreign currency. In these cases the code used was: This is not a telephone topic.

But your problems did not end even if you were one of the lucky few to have a phone. Hefty bribes were also payable even just to get the name and number of the person who could assist you in your quest.

Firstly, you might have a party line, (a ‘twin’, as they were called) whose identity was secret, though occasionally people had managed to find out. It could be someone in the same building, or someone in another district entirely. Only one of you could use the line at a time – so if you had been paired with a particularly lonely person with lots of time on their hands, you might constantly find yourself picking up the receiver to the sound of silence on the other end – especially as calls were charged at a mere one forint a call! And if they did not replace the receiver properly, days might pass when you were unable to use it at all! (Hence the secrecy, as threats were not unknown!)

Secondly, assuming you had a telephone, and even better, had no ‘twin’, you could not be guaranteed a line. The joke went that the Hungarian spy was caught because on making a call, he lifted the receiver and first waited for a line before dialling. Quite regularly, you might also find yourself at the centre of a real ‘party’ line, when two other people would unwittingly already be talking on ‘your’ line, demanding you hang up!

Rain could also frustrate your attempts to make a call. It was widely believed that the Hungarians had bought their telephone technology from Sweden, but had not insulated the lines, and therefore wet weather meant phones were regularly unusable. And woe betide you if you failed, for any reason, to pay your bill immediately. Your phone would be disconnected, possibly permanently.

And all this was if you were lucky enough to have a telphone at all!

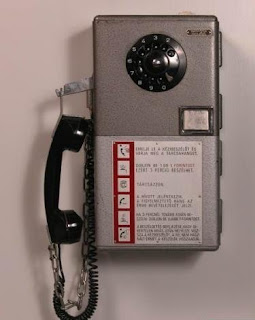

Pity the 90% who had to use public phones! There were two varieties – the yellow boxes for domestic calls, and the red ones for international calls. The string of variables that usually prevented you from making a call are almost too many to ennumerate: the receiver was in pieces; you couldn’t insert the coin; you inserted the coin and it fell through – again….and again…; you inserted the coin but it was just swallowed, and the line remained dead; you got through but the other person could not hear you, in spite of your most frantic screams….It was usually less stressful, and took hardly any more time, to see your friend personally!

After five years, and in our fifth flat, we became the excited owners of a telephone. It was a party line, but our ‘twin’ was a friendly neighbour, so the relationship was amicable. With five years’ experience of making calls in Budapest, I thought I was as much of an expert as any local, and could not be caught out by the vagaries of the Post Office. I was wrong. On returning from a summer visit to England, the neighbour told me that our number had been changed whilst we were away. Not only had we not been notified (see the blog on Information Blackout!), nor could we find any explanation for the change, but we had no idea what our new number might be!

We were to find out soon enough, though, when we received an endless string of calls from people enquiring about the availability of spare parts for their washing machines. We had (inadvertently?) been given the same number as the Hajdu washing machine repair shop! Another service from magyar posta!

Maybe, being forced to endure others’ mobile calls is a relatively small price to pay – at least I can get off the bus or listen to my Ipod!

As with most aspects of modern life, Hungarians have very quickly caught up with western trends, this extending to the ubiquitous use of the mobile phone. In fact, when the large, brick-like contraptions first came into being, there were probably more of them evident on Budapest’s streets than on the streets of London: for one simple reason - because so many people still had no landline telephone!

Possession of a telephone before 1989 was the major selling point for flats. About one in ten people in Budapest owned one, while in some villages it was only the doctor who did. Waiting lists for acquiring a phone were around 12-15 years – not the apparatus itself, but the line. I was assured that the reasons for this were primarliy (if not entirely) political, inasmuch as communications could hereby be both limited and monitored. Many topics were not deemed safe to discuss on the phone, as for example, matters connected with foreign currency. In these cases the code used was: This is not a telephone topic.

But your problems did not end even if you were one of the lucky few to have a phone. Hefty bribes were also payable even just to get the name and number of the person who could assist you in your quest.

Firstly, you might have a party line, (a ‘twin’, as they were called) whose identity was secret, though occasionally people had managed to find out. It could be someone in the same building, or someone in another district entirely. Only one of you could use the line at a time – so if you had been paired with a particularly lonely person with lots of time on their hands, you might constantly find yourself picking up the receiver to the sound of silence on the other end – especially as calls were charged at a mere one forint a call! And if they did not replace the receiver properly, days might pass when you were unable to use it at all! (Hence the secrecy, as threats were not unknown!)

Secondly, assuming you had a telephone, and even better, had no ‘twin’, you could not be guaranteed a line. The joke went that the Hungarian spy was caught because on making a call, he lifted the receiver and first waited for a line before dialling. Quite regularly, you might also find yourself at the centre of a real ‘party’ line, when two other people would unwittingly already be talking on ‘your’ line, demanding you hang up!

Rain could also frustrate your attempts to make a call. It was widely believed that the Hungarians had bought their telephone technology from Sweden, but had not insulated the lines, and therefore wet weather meant phones were regularly unusable. And woe betide you if you failed, for any reason, to pay your bill immediately. Your phone would be disconnected, possibly permanently.

And all this was if you were lucky enough to have a telphone at all!

Pity the 90% who had to use public phones! There were two varieties – the yellow boxes for domestic calls, and the red ones for international calls. The string of variables that usually prevented you from making a call are almost too many to ennumerate: the receiver was in pieces; you couldn’t insert the coin; you inserted the coin and it fell through – again….and again…; you inserted the coin but it was just swallowed, and the line remained dead; you got through but the other person could not hear you, in spite of your most frantic screams….It was usually less stressful, and took hardly any more time, to see your friend personally!

After five years, and in our fifth flat, we became the excited owners of a telephone. It was a party line, but our ‘twin’ was a friendly neighbour, so the relationship was amicable. With five years’ experience of making calls in Budapest, I thought I was as much of an expert as any local, and could not be caught out by the vagaries of the Post Office. I was wrong. On returning from a summer visit to England, the neighbour told me that our number had been changed whilst we were away. Not only had we not been notified (see the blog on Information Blackout!), nor could we find any explanation for the change, but we had no idea what our new number might be!

We were to find out soon enough, though, when we received an endless string of calls from people enquiring about the availability of spare parts for their washing machines. We had (inadvertently?) been given the same number as the Hajdu washing machine repair shop! Another service from magyar posta!

Maybe, being forced to endure others’ mobile calls is a relatively small price to pay – at least I can get off the bus or listen to my Ipod!

No comments:

Post a Comment