Twenty years is a long time – particularly if viewed as half the number of years that Communism dominated the lives of people in this part of the world. Many of the ills bemoaned by those living here - from pollution and poor customer service, to reliance on the state to solve one’s problems, and a poor work ethic - are all ascribed to the evils of the system that cast its shadow on every aspect of people’s lives for four decades.

I may not live to see the close of four decades of freedom, but at this halfway stage I can stand and look back at what has been achieved and what is still left to be done: I try to gauge what has been gained and what has been lost.

Leaving Britain in 1982 and heading for a new life in a totalitarian state was greeted with disbelief by family and friends. At the height of the Cold War, they could neither imagine nor believe that

anything on the ‘wrong side’ of the iron curtain could be better than what we were voluntarily leaving behind us.

Similar perplexity was expressed by Hungarians we came to know in Budapest – surely

everything must be better in our home country; was there some ulterior motive for our decision to abandon the Motherland?

Try as we might, our explanations on both fronts proved largely fruitless. Our letters from home were opened, Paul’s presence and activities in the Music Academy were monitored, and we overheard British Embassy staff voicing doubts as to our real purpose for coming to the country. It seemed that neither Hungarians nor the British accepted that we might have anything other than suspicious reasons for staying. Quite simply, neither side saw anything but hardship and deprivation in communist Hungary.

It would be foolish to assert there was nothing amiss; great swathes of writing attest to the ills of the system as it was. Many foreigners are at a loss to understand why anyone should feel an ounce of nostalgia for those years of communist dictatorship, and comparatively scant sources exist to counterbalance a decidedly lopsided picture.

We found in Hungary a cohesive society where everyone was ‘poor’ (by today’s reckoning) but no-one was destitute. We could all pay our bills without the slightest worry (including the phone bill, if we had one!) Food was plentiful and cheap – if variety was lacking, we nevertheless ate well and without a thought for the cost. Everyone had employment – yes, of course maintained artificially, but it guaranteed an income, an absence of homelessness and a feeling of belonging to the society in which we all lived. The three basics of existence (a roof over one’s head, warmth and food) were supplied at little or no cost.

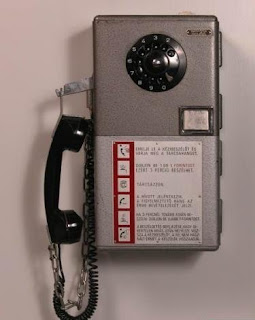

The education system extolled excellence in the form of both grammar schools and vocational training, alongside specialist tuition for anyone with talent in any field from sport to music. The health service had no waiting lists of any sort, and medicines were available at nominal cost. Family life – in the absence of more colourful distractions – remained strong, and friendships thrived in a world where no email or text messaging existed, and where with a dearth of telephones, personal meetings were the usual form of communication. Nursery education from 6 months of age was free, and 3 years’ maternity leave with your job back, was also guaranteed.

There was virtually no crime: life was peaceful, and in a society where work was not taken over-seriously, we had a great deal of leisure – the word stress (

stressz) then being blissfully non-existent in the language!

And if we could not (easily) buy the latest hi-fi or car, books cost pennies, a ticket to the opera or the cinema was a mere 10 forints, and a restaurant meal with a taxi home was within everyone’s means.

The feeling of ‘us’ (ordinary people) and ‘them’ (the Communist Party / Russians) bound even strangers together: all of us living in a system which - through helping one another - could be circumvented or overcome. Those one helped today, could help in turn tomorrow. The result was akin to the camaraderie one reads of in the war.

The abolition of the border opened the proverbial Pandora’s box. The ills we had sought to describe in a vain attempt to rationalise leaving England, such as unemployment, vandalism, a society where the only value put on anything is monetary, homelessness, job insecurity, a fragmenting society where each looked out only for himself (these were the Thatcher years), were suddenly made real.

Unfortunately, the dreams Hungarians had cherished: that the country would become the financial equivalent of Austria, have not come to pass. They have acquired the dark side of western living, without the compensations.

I remember in about 1990 – when political jokes were still a part of everyday life – being asked this one: How is Hungary both a communist

and a capitalist country? The answer: we have communist wages - and capitalist prices….

I am not a political animal. I have just returned from a week in England where almost every news channel was anticipating, and then dissecting the BBC programme Question Time, whose panel included the BNP leader, Nick Griffin. His appearance on the programme was marked by demonstrations and controversy in all sections of society, due to his alleged policies on immigration.

I am not a political animal. I have just returned from a week in England where almost every news channel was anticipating, and then dissecting the BBC programme Question Time, whose panel included the BNP leader, Nick Griffin. His appearance on the programme was marked by demonstrations and controversy in all sections of society, due to his alleged policies on immigration.

‘Why don’t you write about the Post Office?’ asked a friend this week, knowing only too well my fraught relationship with that particular institution over the last thirty years. Were I writing this by hand, the tension and frustration evoked in those memories would be discernible in my manuscript.

‘Why don’t you write about the Post Office?’ asked a friend this week, knowing only too well my fraught relationship with that particular institution over the last thirty years. Were I writing this by hand, the tension and frustration evoked in those memories would be discernible in my manuscript.