The postman in Hungary occupies the equivalent position in the social fabric, to the milkman in Britain. And maybe like the milkman, whose role and importance have faded with the dawn of Tetrapak and Tesco’s, he has been superseded by email and a banking system.

In humorous exchanges, the postman has been credited with a motley band of children who somehow do not seem to have inherited the genes of their parents: those who have red hair (when all their family are dark), or who are any kind of family misfit!

This aside, the Hungarian postman of yore adopted a number of roles: the first was as deliverer not only of letters, but bringer of monies. With no banking system before 1989, it fell to him to deliver pension money on the 2nd of each month. The elderly would loiter on the walkways above courtyards, leaning on railings awaiting his arrival; we also waited for sundry payments for translations completed or recordings done. When the cash was handed over, it was customary to share a small amount of one’s earnings with the postie – always a good investment, in view of the fact that the postman had powers far in excess of those the job would normally incorporate.

As the only person guaranteed to make a daily visit to every building, he was uniquely placed to observe any irregularities in the lives of its occupants. For example, when flats were still state-owned and rented by their tenants, conditions for their ‘inheritance’ when the occupier died, were complex. Grandparents made sure their grandchildren were registered as living with them, because in the event that they had failed to do this, the grandchild had no hope of inheriting the right to rent the flat when he would later need to do so. The ‘flat problem’ in communist Hungary, ecplised every other social problem. Those without this possibility could be condemned to fifteen years on a waiting list before being granted their first state flat.

Most children – naturally enough – lived with their parents. Visits to grandparents were made with varying degrees of regularity to reinforce the pretence, but the truth could not be hidden from the postman. He would know perfectly well the reality, that no child was living with them, since he chatted to all those to whom he took their pensions. It was probably unlikely he would betray anyone to the authorities, but it did no harm to give him the odd ‘tip’ for money or a parcel brought upstairs to your flat door, just in case….

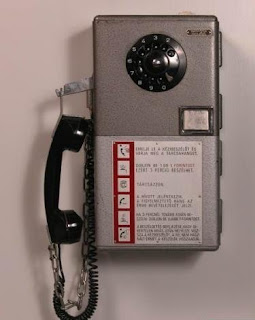

Our own case was similar when we moved to a flat with a telephone. Applications for telephones also incurred waiting lists of twelve to fifteen years. Moreover, they ‘belonged’ to the tenants of the flat, and could be taken with their owners to any new flat they moved to.

Luckily, the previous owners of our flat did not need to take their phone with them, since their new home already had one – a very rare circumstance. Yet the only way we could prevent this most precious of commodities being confiscated from us and given to the lucky person at the head of the waiting list, was to maintain the pretence that the old owners were still resident in the flat. To this end, we had nothing more to do than take the monthly pay-in slips to the Post Office, and pay the bills.

Of course, the postman knew very well the true situation. The old owners had lived there some thirty years, and the postman had obviously had this same round for a similar length of time. Thus, when we moved in, he came up the sixty-odd stairs to introduce himself to us. Having satisfied himself as to what manner of residents we were, he dropped in a casual question regarding the phone. We explained that the old owners were not taking it with them; we would continue to pay the bills. A knowing look passed between us: an unspoken conspiracy.

He arrived some weeks later with a parcel of books for Paul. There was nothing to be paid for this service if the books were posted from within Hungary, and yet I felt I would enquire.

‘No. Nothing to pay,‘ he said, ‘but they are very heavy.’

His meaning was not lost on me. I went to find my purse….

In humorous exchanges, the postman has been credited with a motley band of children who somehow do not seem to have inherited the genes of their parents: those who have red hair (when all their family are dark), or who are any kind of family misfit!

This aside, the Hungarian postman of yore adopted a number of roles: the first was as deliverer not only of letters, but bringer of monies. With no banking system before 1989, it fell to him to deliver pension money on the 2nd of each month. The elderly would loiter on the walkways above courtyards, leaning on railings awaiting his arrival; we also waited for sundry payments for translations completed or recordings done. When the cash was handed over, it was customary to share a small amount of one’s earnings with the postie – always a good investment, in view of the fact that the postman had powers far in excess of those the job would normally incorporate.

As the only person guaranteed to make a daily visit to every building, he was uniquely placed to observe any irregularities in the lives of its occupants. For example, when flats were still state-owned and rented by their tenants, conditions for their ‘inheritance’ when the occupier died, were complex. Grandparents made sure their grandchildren were registered as living with them, because in the event that they had failed to do this, the grandchild had no hope of inheriting the right to rent the flat when he would later need to do so. The ‘flat problem’ in communist Hungary, ecplised every other social problem. Those without this possibility could be condemned to fifteen years on a waiting list before being granted their first state flat.

Most children – naturally enough – lived with their parents. Visits to grandparents were made with varying degrees of regularity to reinforce the pretence, but the truth could not be hidden from the postman. He would know perfectly well the reality, that no child was living with them, since he chatted to all those to whom he took their pensions. It was probably unlikely he would betray anyone to the authorities, but it did no harm to give him the odd ‘tip’ for money or a parcel brought upstairs to your flat door, just in case….

Our own case was similar when we moved to a flat with a telephone. Applications for telephones also incurred waiting lists of twelve to fifteen years. Moreover, they ‘belonged’ to the tenants of the flat, and could be taken with their owners to any new flat they moved to.

Luckily, the previous owners of our flat did not need to take their phone with them, since their new home already had one – a very rare circumstance. Yet the only way we could prevent this most precious of commodities being confiscated from us and given to the lucky person at the head of the waiting list, was to maintain the pretence that the old owners were still resident in the flat. To this end, we had nothing more to do than take the monthly pay-in slips to the Post Office, and pay the bills.

Of course, the postman knew very well the true situation. The old owners had lived there some thirty years, and the postman had obviously had this same round for a similar length of time. Thus, when we moved in, he came up the sixty-odd stairs to introduce himself to us. Having satisfied himself as to what manner of residents we were, he dropped in a casual question regarding the phone. We explained that the old owners were not taking it with them; we would continue to pay the bills. A knowing look passed between us: an unspoken conspiracy.

He arrived some weeks later with a parcel of books for Paul. There was nothing to be paid for this service if the books were posted from within Hungary, and yet I felt I would enquire.

‘No. Nothing to pay,‘ he said, ‘but they are very heavy.’

His meaning was not lost on me. I went to find my purse….